Editor’s note: This feature ran first in our June newsletter Xpresso. To gain access to our top content faster and stay ahead of technology, please considering subscribing to Xpresso.

IN THIS FEATURE WE TAKE A BROAD LOOK AT IMMERSIVE technologies such as VR/AR—scanning across histories, present technologies, companies, and many of the key issues around their success.

Origins of VR

While it may seem that the VR-AR craze emerged only a few years ago, these technologies have had long invention cycles spanning multiple decades which sorted out the many difficulties that make immersive technology experiences so challenging. Even more, the very concepts behind “virtual reality” and the technologies that make it possible go back nearly two centuries.

In 1935 science fiction writer Stanley Weinbaum released Pygmalion’s Spectacles, a story about the main character that wears a pair of goggles that look like a gas mask which transports him to a fictional world where his human senses participate in holographic reality. Here’s a quote from the short story:

But listen—a movie that gives one sight and sound. Suppose now I add taste, smell, even touch, if your interest is taken by the story. Suppose I make it so that you are in the story, you speak to the shadows, and the shadows reply, and instead of being on a screen, the story is all about you, and you are in it. Would that make real a dream?

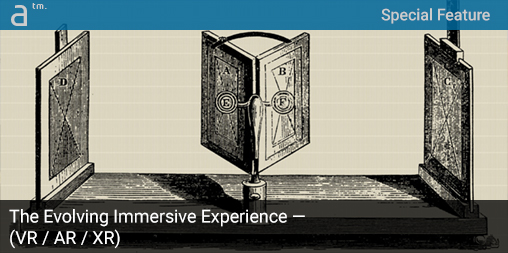

Weinbaum’s character is describing the concept of virtual reality at a level that we actually have not yet achieved in a mass-produced shipping consumer or industrial product. Yet, while this vision from 1935 is remarkable, key technical aspects of virtual reality head-mounted displays (HMDs)—like stereoscopy or what is also known as stereo imaging—first began with Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838 when he was awarded the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1840 for his explanation of binocular vision, upon research that led him to construct the stereoscope.

Sir. Charles Wheatstone’s mirror stereoscope. His research and this instrument won him the Royal Medal from the Royal Society in 1840. In the image above, images ‘D’ and ‘C’ are brought together and combined by the human brain when viewed through lenses focused on two mirrors (‘A-B’) angled at 45 degrees to the images. (Image: Wiki Commons)

His research proved that the human brain actually combines two images (one eye viewing each) of the same subject take from different points to make the image appear as one with a sense of depth and immersion or three dimensions. His Wheatstone mirror stereoscope is shown above.

However, David Brewster who rivaled Wheatstone developed a hand-held “Brewster-type stereoscope” that caught the attention and admiration of Britain’s Queen Victoria when it was demonstrated at the Great Exhibition of 1851. This device used lenses for uniting the dissimilar pictures in 1849, leading to lenticular stereoscopy, which allowed Brewster’s device to be much smaller than Sir Charles Wheatstone’s invention. Brewster’s device, made of wood, resembles the Google Cardboard in some ways.

A Brewster-type stereoscope was enjoyed by Queen Victoria at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The device introduced “lense-based” stere imagery. (Image: Wiki Commons)

These 19th-century stereoscopes would ultimately lead to one of America’s most well-known devices commonly purchased for children—the ViewMaster stereoscopes, which led to the craze for “virtual tourism” which is used in modern VR headsets today. End-of-life patients are sometimes allowed to travel to far-away places using VR as part of their care plans.

While stereoscopy was a critical element of the future of VR, another major piece of the modern-day puzzle was motion-tracking. If a user moved their head looking at the stereoscope-based image there was no sense of movement in the image, those devices only simulated depth and being in a far-away environment (“virtual tourism”), which was the big hit of ViewMasters that took millions of users to special places like the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

Morton Heilig’s Sensorama offered multi-sensory immersive experiences but he could not get funding and support to mass-manufacture his vision and invention.

Morton Heilig, a cinematographer, created the Sensorama, a real VR machine that a user sat in and combined multiple technologies and stimulated the senses. Sensorama combined 3D video, audio, vibration in the seat the user sat on while using the device, plus smell and atmosphere effects like the wind. In many ways, the Sensorama was a forerunner of Walt Disney’s technologies behind their hit Disney World ride Avatar Flight of Passage. Combining so many sensation-based technologies increased the “immersion” into the virtual environment.

Reader Comments

Comments for this story are closed