Brief History of Revit

IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND WHY some of the world’s leading architecture firms signed an open letter lamenting their issues with the presumed world leader in software for architects—Revit—one fact must be contended with right away. Revit is now two decades old. That’s a very long time in the world of software and technology. And that time-frame overlaps two distinct phases within the larger phases of the current digital era, or what technology and economics historian Carlota Perez terms the “ICT Revolution” (Information and Communication Technologies).

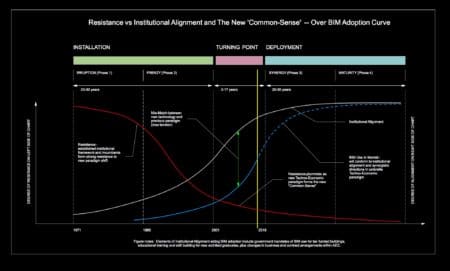

It is important to emphasize the timing of Revit’s existence against the larger developmental phases of the ICT revolution. We won’t get into the weeds on Perez’s well-regarded Techno-Economic paradigm model, a historical and macroeconomics theory that explains the developmental waves of industrial progress since the first industrial revolution. We actually already did that here in reference to AEC and BIM. But in a nutshell, as overlaid against the ICT revolution era, Revit emerged rather late after a two-decade “installation phase” where architects and engineers replaced hand drafting with the newly available technologies of (2D and 3D) CAD. (see image below).

02 – In this chart, we overlay Carlota Perez’s theory model over the stages of BIM adoption thus far. It is important to understand that the “Turning Point” period which always exists in each successive technical revolution is more about social dynamics and social unrest. The Revit open letter is itself a signal that we are currently in the later stage of the Turning Point and social protest movements happening everywhere in western societies also index Carlota’s assessment that we living through the Turning Point in the ICT Revolution.

To make matters worse, the ICT era itself possesses an echo, a kind of mirror image of itself with enhancements based on a second paradigm-defining invention. That invention was the Internet. The ICT Revolution itself sprung from the key invention of the Intel microprocessor in the early ’70s. Steve Jobs distinguished this echo era by calling the first phase of ICT (he used the term computing) the era of productivity applications (eg: Word, Excel, MacDraw) while the next era was defined by consumption applications due to the connection of the Internet (eg: Web browser, Email)

Any application that emerged in the late ’90s or early oughts emerged from the development framework of the era of productivity applications. As such, as Anagnost says in the next article, Revit is 20-year old code built monolithically on a Windows stack. It is not a “modern” application in the sense that it does not meet the accepted definition of a modern application in the SaaS and mobile + cloud-based world we live in today.

Not only was Revit birthed during the high reign of Microsoft Windows—a reign that would be sunset-ted by the mobile+cloud era brought about by Apple’s iPhone—it also must contend with its own weight and development velocity issues. For this, I’ll quote Martyn Day at AEC Magazine in his coverage of the open letter when he says about Revit’s age problems, “…eventually software applications age; years of new layers of features compound to make products cluttered.” Day does an excellent job of detailing the velocity issues that ever-larger applications inevitably must contend.

Revit isn’t the only major AEC software tool that is decades old with zillions of users wrapped around it. But is was birthed at a specific time which aligned its development trajectory in a particular way, and not fully understood reasons it has escaped the modernization code work many of its rivals have undertaken. As we learn in the next article, Revit, as I write this is actively being “recoded” at the guts level, something Autodesk commenced with for AutoCAD over a decade ago. And it took nearly a decade to get Autodesk to its modern app status.

Autodesk’s marketing machine has convinced the contractors that Revit is BIM. Whereas, BIM is actually a process.

Today’s digital business landscape, in AEC or in the larger world, is one with an entirely different set of expectations placed upon software than in the late 1990s or early oughts. Today’s software users expect access to their tools and data from a variety of locations and devices. Even more importantly to the future of software, today’s users are seeking out automation and semi-autonomous and AI-driven assistance. And they are demanding both privacy and ownership of their data, meaning data transportability via industry standards that let users take their data with them.

Against this backdrop, Revit has been constrained by its development history and trajectory (ie: “monolithic and Windows-based), spread thin by Autodesk’s admitted resource limitations, while simultaneously enjoying the Kleenex-brand marketing advantages of the BIM transformation.

The Failures of BIM Competitors?

On many levels, Revit has benefitted tremendously from Autodesk the company, and brand. Numerous sources I have spoken to say that Autodesk’s marketing machine has done a brilliant job of aiding the misnomer that Revit is BIM. “Autodesk’s marketing machine has convinced the contractors that Revit is BIM,” says lain Godwin, AEC IT consultant and former IT director and senior partner at Fosters + Partners, who helped manage the Revit Open Letter movement. “Whereas, BIM is actually a process.”

When industry analyst Jerry Laiserin helped popularize the term BIM (building information model or building information modeling) quickly overtook rival Graphisoft’s “virtual building” terminology in the early part of this century once Revit became the new kid on the block in the AEC software sphere. Both Bentley and Graphisoft would eventually adopt the term BIM to describe their solutions and technology, but nuances of BIM were lost against an AEC audience of Baby Boomer leadership—true digital immigrants who largely represent the “resistance” group from which the ICT Revolution has had to contend.

Throughout the first decade of the new century, the new upstart Revit would benefit from “network effects” vis-a-vis Autodesk AutoCAD. Once bundled with AutoCAD and other AEC solutions, the new BIM solution would gain entry into firms and generate seat counts. As Revit gained traction, slowly the largest firms in the UK—known as the AJ100 List—would begin BIM trials using Revit while simultaneously pushing out their main projects on Bentley’s Microstation software.

I think for the past 10 years RVT has been the de facto standard way to pass your data to consultants. Unless you are in rail or infrastructure, then even there it is inside a file system of choice because DGN supports global position coordinate systems better than any Autodesk product does.

Elaine Lewis, of Cadventure in the UK, a major solution provider to the European AEC industry, and a Bentley solutions provider, told me that five to ten years ago, 85 of the 100 in the AJ100 List firms were using Bentley solutions primarily. While they have migrated to BIM and Revit workflows they have maintained in constant contact with Cadventure for numerous consultant reasons.

“Bentley software has always been extremely good at large scale projects,” says Lewis, “because it works with reference files. That is why the AJ100 list was mostly Bentley.” Large scale projects—the likes of which Foster + Partners has become famous for (eg: Apple Park)—explains why that firm has been a longtime Bentley user. Lewis acknowledges that “technology has moved on since then and there are other good solutions out there” but she adds that “historically that is why Bentley was, and remains, a very good solution to those [large project] environments.”

With the Revit open letter group complaining of underwhelming performance (and on larger projects more so) and poor utilization of multi-core processors, it is surprising somewhat that Bentley has not maintained a larger share of the BIM market. However, it is understandable how it would cede so much of AJ100 List to Autodesk while it began to focus on the infrastructure market over the building market. lain Godwin informs me that of the large practices in the UK, most are still not fully an Autodesk house. “About 30 percent of them have fully moved to Autodesk,” he says, “but 70 percent are probably still in a mixed environment.” This statement reflected my discussion with Elaine Lewis of Cadventure.

The Dominance of Revit

Regardless, both perception and the open letter itself reflect the dominance of Revit in AEC in the UK, US, and Australian markets, among others. “I think for the past 10 years RVT has been the de facto standard way to pass your data to consultants,” says lain Godwin. “Unless you are in rail or infrastructure, then even there it is inside a file system of choice because DGN supports global position coordinate systems better than any Autodesk product does.”

I think Autodesk did a really good job of providing a solution that was relatively easy to use and provided a demonstrable BIM solution fairly early on.

While BIM competitors have reacted in different ways to Autodesk’s “network effect” advantages, its ability to leverage AutoCAD wasn’t always its best weapon. The AJ100 List is a case in point. These firms went from Microstation to Revit. “I think Autodesk did a really good job of providing a solution that was relatively easy to use and provided a demonstrable BIM solution fairly early on,” says Elaine Lewis. “And if you recall the first take up of Revit was the early 2000s and we were in a recession and it was an opportunity for people to say ‘what are we going to do while there is no work? Let’s look at how we organize ourselves…how do we come out of this hiatus stronger, better, different?’ And I think Autodesk did a brilliant marketing job. It’s really the Betamax-VHS comparison, isn’t it?”

Advertisement

Elaine Lewis reminds me that Betamax had the superior quality but VHS won the day because they had the most media titles. In the AEC industry, the equivalent of a media title isn’t necessarily the equivalent of plugins or third-party add-ons—though all of them count also. It’s what we call “the ecosystem.” And available skills are a part of the ecosystem. “Skills in the market are a constraint,” says Godwin in discussing Revit’s market share leadership. “How do you find ten ArchiCAD guys or gals?” he says. “They aren’t necessarily learning it in college. They may not be learning Revit in college either these days…maybe more Grasshopper and Rhino.”

Bentley and Graphisoft may certainly protest the notion that Revit has come to dominate the market due to their failures. It’s understandable given how well “network effects” intrinsically benefit incumbents. We saw this play out with Netscape and Microsoft’s web browser and the United States Government’s anti-trust case against Microsoft two decades ago. Bundling advantages and network effects don’t make things a fair fight and everyone knows it. And the losers in most such cases are customers. But when a rival has such advantage competitors need to react appropriately and find a way forward.

In the case of Graphisoft, it concentrated on technical superiority across a range of key issues meaningful to users. Its patented delta technology in its BIM server and its award-winning BIMx mobile app set Graphisoft apart from the industry. Bentley focused on and grew in infrastructure and today stands in a very strong and opportunistic place given massive infrastructure renewal. The company just recently went public. Other competitors like Vectorworks grew out in starfish formation, reaching with new legs into concentrated specialties and new industries, all with BIM technology at the core.

Carlota Perez refers to this phenomenon of spreading as witnessing a “full constellation” of how ICT expands into new industries, systems, and infrastructure. This is a normal part of the unfolding or process of a Techno-Economic paradigm transformation.

next page: Early Warning Signs for Revit

Reader Comments

Comments for this story are closed